The themes of eating in general and the filching of food in particular are pervasive in Charlie Chaplin’s films. A Chaplinesque instance of food filching, such as in The Immigrant (1917), may be “an utterly unreal comic situation,” but it also “subtly suggests a form of revolution,” as Devin Orgeron and Marsha Orgeron write. (1) In Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936), the focus of this essay, the leitmotifs include man-eating machines, foraging for food, and consuming materialism.

I wish to tease out an inverse counter-current to these forms of ingestion, which together constitute a revolution by rejection. (2) Men swallowed by machines are spit out in transfigured form and engage in sabotage; the filching of food by the poor disrupts the social order and calls into question its morality; and the apparent devouring of consumer dreams is in fact a humorous/satirical undermining of their logic.

Chaplin’s critique of the machine age is rooted in a history of industrial sabotage. It also foreshadows many artistic responses to the “megamachine,” from George Orwell’s “Big Brother,” to the monkey-wrenchers of Edward Abbey and T.C. Boyle, to the visionary city symphony Koyaanisqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1982), in which humans are enslaved by the technology that is their grid and host. (3)

Modern Times is Chaplin’s last “silent” film, and a last bow for his “Tramp” character, which had made Chaplin the world’s most famous man in the 1920s. After the 1931 premier of City Lights 9131), Chaplin went on a world tour, meeting with many leaders to discuss the pressing issues of the time. In newspaper articles and later an autobiography, he described his travels.

At a meeting with Mahatma Gandhi, Chaplin said he was “confused by your abhorrence of machinery,” which could “release man from the bondage of slavery,” if altruistically used, Chaplin argued. Gandhi replied that machinery had made India dependent on England, so “we must make ourselves independent of it if we are to gain our freedom.” (4) By the time he began production of Modern Times (then titled “The Masses”), Chaplin was declaring: “Machinery should benefit mankind. It should not spell tragedy, or throw it out of work.” (5)

Chaplin wanted The Tramp’s swan song to address the pressing issues of the Great Depression and pre-WWII years: unemployment, food shortages, the Fordist routinization of industry, and repression of political protest. (6) Chaplin’s ability to combine hilarity with pathos reached classic heights in this film. But inside of Modern Times’ factories, a surveillance worthy of Orwell and Michel Foucault runs things, while on the streets a police state squashes all protest.

Chaplin shows drug-running in prisons and Communist marches; he lampoons religious do-gooders and glorifies food theft by the poor. Like most Chaplin films, Modern Times is episodic, but a meta-narrative emerges: “the spirit of the machine age” is double-voiced; machines mechanize human beings, but the “weapons of the weak” are available, (7) and the human spirit can break out of its confinements, providing not only comic relief but utopian models during dystopian times.

I will frame my reading with comments from two students about the Tramp’s interaction with machines. In an opening sequence when factory machines are sped up to an inhuman pace, the only way to keep up with the pace was to go inside the machine. Later, the Tramp feeds a mechanic who is trapped inside a machine during lunchtime. Everything in the camera’s view is eating. (8) That of course includes the “man-eating machine.” These observations are openings onto Chaplin’s visual comedy about the dangers of being “eaten alive” (9) in the machine age, and his tribute to the spirit of human resistance and innovation which endures, even in the belly of the beast, or in the face of efforts to regulate and mechanize human behaviour.

Much of this metanarrative is signalled in the establishing shots. First there is a long shot of a clock tower: industrial time rules this world portrayed here. Chaplin then shows a flock of sheep rushing through a corral. In the center is a black sheep. Next workers rush out of a subway. Workers are like sheep, we infer, but Chaplin’s tramp will be the black sheep who breaks norms and demonstrates escape routes from sheepish or machine-like behaviour.

Ingestion and Dysfunction in Man-Machine consumption

I want to first focus on an early scene at the Electro Steel Corp. when a machine short-circuits while attempting to force-feed the Tramp. Chaplin dated this idea to 1916, a “satire on progress” in the form of a trip to the moon for the Olympic games. The Tramp might as well be the man in the moon in the factory. That the “feeding machine” gags travel well is evident in the Cuban short “Por Primera Vez” (“For the First Time”, Octavio Cortazar, 1967), in which Cubans at the cinema for the first time laugh uproariously at the segment in which the machine spins a corn cob in Charlie’s teeth. (10) This scene reads almost like a travesty of enduring a drill in a dentist’s chair. The failed attempt to force-feed corn to this non-industrial man helps construct the film’s meta-narrative.

Chaplin’s Tramp will not become a man of corn in the sense of the critique of industrial food as developed in King Corn (Aaron Woolf, 2006): a perversion of traditional corn culture which has produced corn-fed people whose very molecular structure and thought patterns reflect the industrial foods they eat. (11) Charlie the Tramp would eat anything put in front of him, but Chaplin the man was a vegetarian, and his critique of the machine age extended to industrial food, as this scene implies.

This scene also foreshadows later sabotage. Although the tramp is grateful for the free food, and is not trying to “monkey wrench” the feeding machine, this machine goes haywire. It may have been defective to begin with, but something here doesn’t compute: the Tramp is wired differently from the more regimented workers the machine was designed to feed. It’s almost as if the machine cannot process the Tramp’s free spirit, and blows its gaskets in the effort. There is a further foreshadowing in this scene, when the machine shoves steel nuts into his mouth. As Russ Castronovo observes, “before Chaplin is swallowed in the belly of the industrial beast, he finds the machine inside his belly.” (12) Every time the machine tries to swallow or mechanize The Tramp, we might expect he will break down, or become like the machine. But it is the machine and factory system which breaks down, when it cannot digest Charlie’s Tramp.

The scene in which Charlie slides into the machine’s gears is iconographic, a larger-than-life picture that has taken on a life of its own. (13) Following the suggestion that one can only keep up with the machine by going inside it, I want to sketch some implications of this “inside job.” The fullness of what is denoted and connoted in this scene seems inexhaustible. Let us start with a couple of forms of denotation.

He squirts oil on workers and authorities (both are machine-line) to render them ineffective while he continues his sabotage, or escapes. Sensing that the workers cannot think past their mechanization, he uses the machine to distract them. This is not mere sabotage: it is monkey-wrenching as a spirit of play. It creates joyous havoc, disrupting the dehumanizing pace and design of the machine. Even when the tramp is fleeing the police and re-enters the factory, he still punches in. He is not trying to destroy industrial time. But Chaplin brings the insouciance of the music hall, as well as an anarchistic sensibility to his mise-en-scène, to the staging of modern times. Subsequent scenes seem to indicate that as long as one maintains an ability to improvise and a focus on eating well, then in the battle between man and machine, a sort of “separate peace” can be achieved.

The second “machine-eating” scene occurs when the Tramp goes back to work because he wants to buy a “real home” for “The Gamin” (Paulette Goddard). This is a final effort to function within an institutional context; one must read it in relation to a string of earlier failures. After his breakdown, when released from a hospital, he is swept into a series of misadventures: accused communist leader; a hero who foils a jail-break while (inadvertently) high on cocaine. Then he “gums the works” in one job after another, inevitably damaging (or pilfering) the merchandise. His only successes are in finding his way back to jail (a safe space) and charming Gamin. For her, he secures a job as a mechanic’s assistant, but he is such a klutz that no equipment is safe in his presence. He destroys his boss’s tools and then manages to get him stuck inside the gears of another machine. At lunch, he decides that feeding the mechanic is more important that extracting him from the sharp-toothed gears. The Tramp will not stop eating, after all. When he stuffs a stalk of celery in the mechanic’s mouth we can see: everything in the camera’s view is eating.

What are the implications of a mechanic being fed by the Tramp, who is outside the machine that has eaten him? Timothy Corrigan’s comments on perspective in mise-en-scène seem applicable here. Corrigan focuses on the purpose of mise-en-scène, or, all that is put in the frame. This ordering “is about the theatrics of space as that space is constructed for the camera.” The construction of the overall image in a shot is done with a theatrical perspective in mind: perspective in mise-en-scène “refers to the kind of spatial relationship an image establishes between the different objects and figures it is photographing.” (16)

Chaplin’s theatrics of space suggests a particular kind of inter-relationship between the machine and the two men who are working on it, or being devoured by it. Keeping in mind the “ethical inversions” which predominate in this film, (17) one might ask re: the theatrical relations of this scene: who’s in charge? The master mechanic ought to be in charge. But he is imprisoned in the machine, at the mercy of a bumbling worker who is his inferior, in terms of technical competence. Charlie the Tramp in Modern Times is somewhat like the Juan Bobo of Puerto Rico, the town fool who can never get things right. (18) Yet Charlie has “mother wit.” Unlike that Bobo, Charlie’s apparent ineptness in practical matters serves as a critique of the limits of rationality. If the Tramp’s bumbling is well-meaning and unconscious, it serves the conscious designs of the film’s creator. In that sense, Chaplin the multi-millionaire masking as a down-and-out indigent is a forerunner of a very different sort of bobo—a bourgeois professional who espouses bohemian values. (19) Chaplin can afford to identify with the poor because he lives amongst the rich and privileged. From that safe distance he has made a fortune with his representations of the underclass everyman. But in the Tramp’s last appearance he gets off some parting shots at a new world order that marginalizes and indeed criminalizes all that is not mechanized.

An inversion has taken place here, and the intern-inmate is clearly in charge, at least for the moment. He re-establishes a set of priorities which have been crowded out by the machines, and the mechanized men who run them. Foremost amongst these priorities are the need for down time (indeed, work stoppage), and time for communal dining. Something like the innocence of a child’s perspective is evident, but re-ordered through the sensibility of an adult who is both politically engaged, and keenly attuned to the bottom line of entertaining a mass audience.

The man-eating-machine theme came to Chaplin at age 12. Apprenticed to a printer, he found himself dwarfed by a huge printing press. “I thought [it] was going to devour me.” (20)As an adult he reframed this view. Charlie is a trickster (playfulness is the essence of monkey-wrenching), and the machine has swallowed something indigestible, giving it indigestion. In the second lunch-time feeding, all but the mechanic’s mouth has been immobilized. If in the earlier scene, the machine-men had tried for force their workers to ingest progress, (21) on this lunch break, Charlie has engineered a bit of humble pie. Work and the irascible mechanic’s mouth are brought to a standstill. Soon this scene devolves into something like a loving son feeding his invalid father. That he first attempts unsuccessfully to feed the mechanic through an oil funnel, and then successfully through the opening of a whole cooked chicken, seems to suggest the need for both mechanic and machine to be brought closer to natural processes.

Chaplin is prescient in his representation of the struggle for food, and to control its distribution, in the machine age. (22) But this portrait hardly romanticizes leftists or labour unions: no sooner is the confining lunch hour over, when another worker rushes in and announces that they are on strike. So Charlie’s latest job evaporates in less than a day, just like the others.

In Modern Times, both marginalization and attempts at integration centre on food. Hunger and the dynamics of communal dining are central to three scenes on which I will focus:

– Lunching with a drug-smuggler in prison

– Pilfering: bananas, bread, and free-loading

– Dining with the Gamin in imagined and real ‘ideal homes’

Nose Powder in the Prison Cafeteria

After the post-breakdown Charlie is released from the hospital, he picks up a red flag which falls off a truck, and finds himself “leading” a march. The signs declare “Liberty or death,” and express “solidarity” in several languages. Time-honoured ideals, one might think, but of course agitating for freedom or siding with the working class has long been criminalized and painted as subversive in the U.S. Misrecognized as a communist leader, Charlie is tossed in jail with common criminals. The jail scenes provide a variant on the theme of going inside the machine in order to keep pace with it. The pace here can only be sustained by criminality, as when Charlie ingests “nose powder” which a criminal beside him has dumped in the salt shaker. Charlie foils a jail-break in a coke-fueled fit of heroism. He thus gains the status of a “working class hero,” and an (unwanted) early freedom. He also wins a personal episode of the “Bread wars” while high.

Earlier he had filched small nibbles from his burly cell-mate through guile and trickery. But only while high on cocaine does he muster the manly force needed to take the bread for himself. Thus he is doubly rewarded, both by the authorities and by the convicts, for his ingestion of a banned substance. But his “inside job” merely lands him on the street, where “appetite appears to be linked with guilt and criminality as a condition of modern culture.” (23)

Food-filching and free-loading

The Gamin first appears on-screen as a desirable thief, making Robin Hood gestures and striking pirate postures. She cuts bananas on a boat, and then tosses them to hungry urchins on the dock, knife clenched in her teeth. A good-looking pirate indeed. Her redistribution of wealth is immediately comprehensible, given what we see of her poverty, and what we soon learn of her destitute family. But the boat and the bananas are private property. When the owner sees her, she scampers to safety, and then engages in another, gratuitous form of trespassing: she eats the banana in his view with defiant relish, a sexual undertone being perhaps a part of her taunting.

Like the Tramp, the Gamin is constantly dodging policemen, but she also flees from child welfare officials after her father is shot in a street protest. She never seems to eat anything that is not stolen, but the “theatrics of space” tell us that this is her due.

While the Gamin’s thievery is suffused with pathos, The Tramp’s shoplifting career is played for laughs. But these barbed laughs plant a subtext about the intertwining of appetites and criminality in modern times. The homeless soul-mates are brought together by a stolen loaf of bread. The Tramp tries to take the blame for her theft, which is typical of his gallantry towards women. But it is also self-interest: a ploy to go to jail. It is worth noting that it is actually the policeman who makes off with the bread. When the police discover that Charlie’s guilt is fictional, he is abandoned in front of a cafeteria. His quest for free food and shelter is realized by free-loading in the cafeteria, after which he enlists a policeman as accomplice. Called to witness Charlie’s inability to pay the bill, he sends the Tramp back to jail—on a full stomach.

The free-loading becomes a joint endeavor after Charlie, fantasizing about a life of abundance in a perfect home, declares that they will secure such a shared abode, “even if I have to work for it.” Opportunity knocks when Charlie secures a job as night watchman in a department store. No sooner has he clocked in than he smuggles in the Gamin, and hustles her down to a soda fountain, where she can load up on empty calories. As at the factory, Charlie makes the department into his playpen—and into a penthouse for his new love, who can wrap herself in furs and sleep on a luxury bed.

Have they “swallowed consumerism”? They are trying on new identities, or new masks, like kids in a playhouse. When the Gamin dons a fur coat she also sports glamorous makeup, as if she were suddenly Cinderella. Charlie glides on a pair of roller skates, as if in a state of grace. But unattainable identities are soon shed like borrowed clothes. Some burglars surprise Charlie, whose knees buckle; one shoots, but only opens holes in a cask of rum. Scared stiff, the Tramp stands in front of the streaming rum with his mouth open. In short order he is in another state of altered consciousness. One of the intruders recognizes Charlie from the steel factory, and soon they are immersed in drunken camaraderie. Meanwhile, the glammed-up Gamin looks like a dream as she sleeps in the lap of luxury. Life on the lam is an intoxication, it seems.

When the store opens the next morning. Charlie has slept under a pile of clothes. A lady shopper tugs on a white shirt, which turns out to be the Tramp’s. When he is extracted, shoppers and the management are appalled, and Charlie and his Cinderella are unceremoniously booted out, where Charlie is carted off to jail once more. The shirt-tugging episode, read symbolically, suggests that consumers want goods produced by or services provided by the underclass, but they do not want the workers themselves. They do not want to be reminded of the presence of those whose flesh and whose labor underwrite their consumerist convenience and leisure.

A Little Taste of Paradise—in search of the “perfect home”

The theme of eating at home with one’s beloved as an unattainable paradise plays out in two parallel fantasies. The first home is imagined by Charlie, while the second is a depression-era shanty claimed by the Gamin. But in both scenes the momentary bliss experienced by the characters is dependent on a shared suspension of disbelief.

Enacting domestic happiness begins with first imagining it. Charlie’s fantasy of suburban bliss occurs after the couple is flung from a police wagon onto the streets (spit out by a machine again). (24) The pair had been arrested for theft—the Gamin’s bread; the Tramp’s super-size meal. Fugitives from justice, they wander into a suburban neighborhood and sit on a curb, where they witness a display of exaggerated marital bliss, with a deliriously happy housewife kissing her husband goodbye as he heads for work. What Charlie describes for the Gamin is a parody of the dream life of sub-urban abundance that was even then luring young professionals off the farm, or out of the cities. Returning home to his apron-clad lady, Charlie can reach into a window and pick an orange or grapes. He calls a cow which milks itself. His woman serves him a steak.

As he is cutting the meat, the “real” Gamin calls him back to reality. A policeman is standing over them, demanding that he keep it real. They are on private property and have to beat it.

Drawing on Gerald Mast’s brief discussion of Chaplin’s use of dream imagery, (25) David Lemaster argues that we should recognize “the importance of dreams [and fantasies] for establishing a sympathetic pity between Charlie and the audience.” In Lemaster’s view, this “motif is actually one of Chaplin’s favorites for further defining Charlie the Tramp’s mask.” (26)

That the Tramp wore a mask that had evolved into a more socially engaged form should be obvious, if we see the film in biographical as well as historical context. In My Autobiography, Chaplin recalled a period of depression and “continual sense of guilt” as he lived the Hollywood high life in the early 1930s. He was troubled by “the remark of a young critic who said that City Lights was very good, but that it verged on the sentimental and that in my future films I should try to approximate realism. I found myself agreeing with him.” (27)

Modern Times, then, was Chaplin’s effort to “approximate realism.” It was a tenuous approximation: Chaplin stubbornly adhered to silent film nine years into the sound era, and sentimentality was ingrained in his character. But as David Robinson’s biography shows, Chaplin was becoming radicalized during 1930s. (28) The Tramp’s “mask” in Modern Times was in keeping with the spirit of the times. The Tramp had long shown a proclivity to bend or break the law, and to live on the fringes of respectable society—close enough to pick off pretty young ladies, but far enough to avoid accountability for either his rule-flaunting or his skirt-chasing. In Modern Times the Tramp evokes our “sympathetic pity” both because of his evident longing for domesticity, and because of his discomfiture with the machine age. His fantasy about the abundance of a suburban Garden of Eden expresses a more politicized satire. We recognize the exaggerated nature of this fantasy, and our laughter has more bite if we see a piece of ourselves in this sketch. Most of us buy into such dreams, to some degree. Even though reality keeps snapping us back, such dreams of romantic or consumer bliss often prove stronger than reality.

But Chaplin more than skirts around realism in staging the other side of paradise—the Gamin’s “perfect” shack. In Philippe Truffault’s special feature Chaplin Today, Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne usefully compare this humble abode to Depression-era shanty town shacks. (29)

The shack interlude takes place 10 days after Charlie has been carted off from the department store, when the Gamin waits for him when he is released from jail. They stand outside the shack and gaze at it as if it is Zion. No sooner has Charlie stepped inside and pronounced: “It’s paradise,” than a board falls and clocks him on the head; the flimsy dining table collapses, and part of the roof caves in. “It’s not Buckingham Palace,” she acknowledges. But the day ends with their illusions and their innocence intact, the Gamin sleeping in a pallet on the floor, the Tramp like baby Jesus in the manger, curled up amidst some hay in a shed.

The key sequence in the shack occurs the next day. Charlie scolds the Gamin for stealing food, and she winks—Modern Times’ attitude towards theft by the poor. The Tramp’s chair falls through flimsy floorboards. No problem: this is a moveable feast; they just move the table and start again. But their house’s instability is the flipside to the unreality of the Tramp’s fantasy of domestic bliss. There is no room for them at the inn of modern times.

Reading the newspaper, Charlie sees that the factories have re-opened. Interrupting their meal, he dashes off to seek employment, wanting to buy a “real home.” By the skin of his teeth, he secures the mechanic’s assistant position which will be interrupted by a strike. Leaving the factory, Charlie once more has a run-in with a policeman, and is carted off to jail yet again.

When he is released, the Gamin has found him work in the café where she is a dancing waitress. The communal dining here is in vibrant contrast to the kinds of eating we see in the rest of the film. The environment is a throwback to Chaplin’s music hall roots. It suggests that the domain of entertainment is their only home. But this will not be permitted them: welfare officers catch up with the Gamin, and they make a vaudeville-style escape. Short of a performance space, there can be only one home for the Tramp: the road. Chaplin fans have seen this exit into a liminal space often: literally straddling two nations that cannot be his home at the end of The Pilgrim (1923). But on departing the silver screen forever, he sets off with his girl. The saccharine rendition of the “Smile” theme masks what is in fact a bittersweet end to this attempt at socially relevant “comic realism.” The Tramp and his love have turned their backs on modern times, and hope to find food, shelter and sustenance in some other social order.

Conclusion

I earlier suggested that Modern Times’ response to the problematics of consumption—devouring machines, a food crisis, and consumerism—together constituted a sort of revolution by rejection. To fully define and explore the implications of that term is beyond the scope of this essay. But I want to sketch its meaning, and suggest how this might shape our assessment of Modern Times in relation to Chaplin’s career, and film history. Two questions I would pose regarding Chaplin’s comedic revolution by rejection are, what is being rejected? And is that rejection revolutionary?

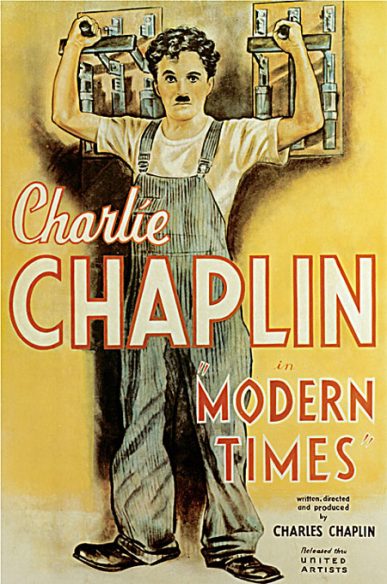

The term revolutionary has been devalued through over-use in the realm of advertising and right-wing politics. I will apply it narrowly to a work of art that satirizes an economic and political order. Revolution is “momentous change in a situation,” or “overthrow of one [order] and its replacement with another,” in political terms. Chaplin is concerned with an economic counter-revolution, the draconian imposition of a Taylorite regime. (30) And in Modern Times, he is keen to dramatize the deleterious effects on the poor of the machine age’s “momentous changes.” The face of what he rejects is devotion to profit so extreme that even a trip to the bathroom is monitored. Chaplin also rejects a criminal justice system which in Modern Times harasses the poor, and prevents a just distribution of resources. But Chaplin also is rejecting most of the “sound revolution” which “overthrew” film’s silent order. It produced momentous changes which Chaplin primarily portrays as negative, like the intrusive voice of despotic authorities. The question of whether this rejection is revolutionary cannot be answered objectively, in social science terms. But as a work of art, this is a “biting satire.” There is a Trojan horse quality that Chaplin folds inside the physical comedy. As with the image of feeding the mechanic who has been devoured by a machine, deeper symbolic levels may be more apparent in the stills. The photo used for the film’s poster conveys the multi-voiced quality of Chaplin’s symbolism. Here the Tramp is monkey-wrencher, ready to wreck havoc on the machine. Yet this pose also seems to echo Samson, about to pull down the pillars of his enemy’s temple. Yet while Samson’s woman blinded him, the Gamin gives Charlie a vision of home, and a reason to go to work. He can no longer swallow the machine age’s martial law, but marital love gives meaning to work and play. Yet again, this could be interpreted as a crucifixion pose—“nailed” to the machine. And yet, for an optimist, this could be the silent rebel raising his arms in triumph.

Our retrospective view of this film must be shaped by the final image Chaplin chose: not the Gamin going to a convent, as Chaplin first filmed it, but the couple heading off towards an empty horizon together. This is similar to the iconography of the Western, and one might argue that the flight into a supposedly utopian anti-social nothingness is reactionary, at heart. Yet there is also something archetypal here about prophets who turn their backs on a corrupt society, and go to the wilderness seeking new vision. In cinematic terms, I think that other generic traditions besides the Western, or the road movie, are a propos. Charlie and the Gamin are “the only two live spirits in a world of automatons,” wrote biographer David Robinson: “spiritual escapees from a world in which [Chaplin] saw no other hope.” (31) The conclusion of Chaplin’s last silent film is a forerunner of the cinematic “Last Man on Earth” tradition, which became a major genre from the 1950s on. What later generations of filmmakers would process primarily through horror and melodrama, in the post-apocalyptic imagination, (32) Chaplin foreshadowed through comedy, in a pre-apocalyptic satire of machines and their guardians run amuck. There are ironies in Chaplin’s representation of an escape from modernity, while he was sleeping with Hollywood starlets and hobnobbing with world celebrities. But this ending is also prescient of his rejection in the U.S. during the era of anti-communist witch-hunts, and his exile in Switzerland. (33)

In its visual imagination, Modern Times is one of the city symphonies which have represented the ways in which sped-up assembly lines shape humans and human society. In a cinematic timeline, Modern Times is close to the bottles of milk in Berlin, Symphonyof a City (Walther Ruttman, 1927). But in its visual ideology, it is closer in spirit to the flows of traffic, energy, and consumer goods in Koyaanisqatsi which, much like Modern Times, are both dystopian and euphoric. Both Modern Times and Koyaanisqatsi give a sense of the hallucinatory quality of our life on a template determined by machines. But both allow for much more benign, even celebratory interpretations. Finally, in addition to being a forerunner of the monkey-wrenching tradition, Modern Times is a fountainhead of an ever-growing body of cinematic work which explores the interpenetrations of humans and machines. This has become a veritable cinematic obsession: the machines we have created as servants have increasingly not only become our masters, but have colonized our bodies and our very imaginations. All filmmakers who explore this dynamic are, directly or indirectly, in Chaplin’s debt.